This is part 4 in a series on walking tours of Johannesburg. While other cities also offer guided tours, Jozi is unique in my mind as a place where people will group together, with or without a guide, to visit places that they normally wouldn't. Whether for safety in numbers, unfamiliarity or companionship, it's a thing here.

|

| Gerald, our tour leader, making a point |

I met

Gerald through my friend

Heather. He is the author of the definitive Jozi guide -

Joburg Places and Spaces 2.0. At long last I get to take part in one of his walking tours around the regenerated CBD. We meet in the current flavour of the month suburb of Braamfontein with its

Neighbourgoods Market and the Lomo Gallery as well as an upmarket bike shop. It has everything a city borough needs to attract the better-off hip crowds of Joburg thirsty for new weekend venues: student bars, start-ups and refurbished condos.

|

| Neighbourgoods Market in Braamfontein |

Grabbing some delicious biltong from the market we set for our six hour walk to see the CBD regeneration. Yes, six hours, but as Gerald points out, there are lots of opportunities to sit and listen to his story, or to gaze at the view, or to have a rest on the bus between destinations. The

tour is offered most weekends, together with another walk from Newtown to Maboneng.

|

| Gerald explaining the layout of the CBD |

Our tour today comprises of a German family whose son lives locally, a Portuguese couple of photographers - he lugs a tripod and heavy camera from shot to shot - and two older Jozi couples giving wistful insights into the history of their home town.

|

| The view from Randlords |

Before we set off Gerald gives us an introduction to Braamfontein, the CBD and general Joburg history. With the historical Kitchener's Hotel pub behind us and the freshly renovated

Play Braamfontein store fronts in front of us, Gerald takes us through his theory of cities as microcosms of a country. The struggle for political power, for economic improvement, for cultural dominance, all this is played out all over South Africa, and in a concentrated form, in Joburg.

|

| The view from the ladies - no, really! |

We walk down the street to Randlords, one of the many private rooftop bars dotted around the city. The 22nd floor is one great window to the skyline, currently being set up for a wedding of hundreds. There is an elaborate deck with cushioned beds for lounging behind a glass bannister. There is even a swing for the playful-minded. The views south across the railway lines towards Newtown, east over the green suburbs to Brixton tower and the slag heap remnants of the gold mines, west to Hillbrow and the CBD are stunning, giving us a taste of what's to come.

|

| In the midst of the city |

We meander our way through Braamfontein to the Rea Vaya bus stop at Park Station at the western end of Braamfontein for our drive to First National Bank in the heart of the city. The

Rea Vaya, together with the Gautrain, are Joburg's latest addition to its frankly pathetic public transport system. This is a driving city, and if you can't afford a car, you are reduced to taking the crazy minibuses. They are dangerously driven, overcrowded and feel themselves above traffic rules, but they are cheap and run back and forth to Soweto. The Rea Vaya buses on the other hand have the potential to transform the public transport scene. They run on routes currently serviced by mini taxis, which made them controversial to set up (the mini taxi racket is highly profitable and tightly controlled by private bosses, which led to

violent demonstrations, strikes and threats when the bus system was first implemented), but in its own pragmatic fashion the bus company has contracted the routes out to the former mini taxi owners, and employs the taxi drivers as bus drivers. There are still some problems, resulting in shiny new stations being boarded up while contracting disputes are resolved, but in the city at least the buses are running more or less on a schedule.

|

| Street trader selling peanuts and underpants |

The bus arrives as soon as we get to the station, a cool sleek glass container with ticket barriers at either end. A sign tells us of all the activities that are not allowed at the station: no eating, no hawking, no waiting, no littering, no graffiti, no flyposting, no music, no smoking, no skate boarding, no guns, no dogs. One symbol of a hand is mystifying: No smacking? No waving? No gloves?

|

| All the activities that are not allowed on the Rea Vaya |

There is a smart card system in development, but for now we get paper tickets. The clean, new, fast bus (it runs in dedicated lanes through the CBDs grid) takes us downtown to the first of the regenerated areas. The

Kerk Street development used to be a rough informal market street, but now has French-style open roofs for the traders and hair braiders stretched along the centre of the pedestrianised street. Both sides are lined with mainstream shops selling fashion like any other shopping street.

|

| Braiding supply shops |

We stop at the bottom of the street next to a row of fruit and veg stalls to listen to Gerald explain the concept of public area regeneration. The premise is that since the council can't afford to renovate the whole CBD, it would improve the public areas to encourage private capital to come in and take over the run-down buildings. So far the city council has made good on the promise of making the streets of the CBD safer and more pleasant, and slowly businesses are moving back and transforming the dilapidated office blocks, many of which have previously been squatted. It's a huge struggle against the inertia of decay. Despite the new paving, the numerous pieces of street art, the pragmatic accommodation of informal traders, there are still plenty of potholes and broken kerbs. I see some of the grand old city buildings have been rescued or replaced with marble shininess, but there are still plenty of ruins with smoke-blackened window holes, graffiti-covered walls and boarded-up shop doorways. It's a long and slow process.

|

| Hair braiders on Kerk Street |

We proceed up Eloff street, once the fashionable shopping mall of the CBD with the most expensive properties, now slowly recovering. The new buildings of First National Bank nearby are bringing flush shoppers back into town. The kerbside is clogged with street stalls selling underpants and socks, bags of sweets and phone credit, cheap jewellery and pens. Women sit on wobbly stools having their hair braided.

|

| Markham's Department Store |

We hear about the Markham building, an elaborate wrought-iron clock tower topping the oldest department store in the city, about the CNA headquarter, a once stylish five-storey corner block now boarded up and abandoned. We stop at the famous Rissick street post office, built by Paul Kruger to show the British that an Afrikaaner government could be as sophisticated as the Empire. Now a burnt-out shell after a 2009 fire, it was going to be demolished until a campaign to save the historic building forced a rebuilding project. At catty corners sits the grandly white Mutual Insurance building. Equally significant for its Edwardian building style, it, too, was going to be demolished, and will now be renovated and improved.

|

| Rissick Street Post Office |

This is something of a theme: there seems to be absolutely no sense of architectural heritage here. Amazing historical buildings are simply abandoned until squatters make short work of the structure, and then pulled down to leave an empty lot that can only hope to survive as a parking lot, or have an anonymous glass and granite edifice parked on it. The CBD is filled with ugly sky scrapers from the bad old days of apartheid, the fatally style-deaf 70s have left their legacy, but there are also still some elegant Art Deco affairs, some late Victorian and Edwardian edifices of the Empire age, and some stylish 60s modernist blocks. No-one seems to think it important to preserve them.

|

| Another intriguing architectural style, representative of 60s Apartheid paranoia |

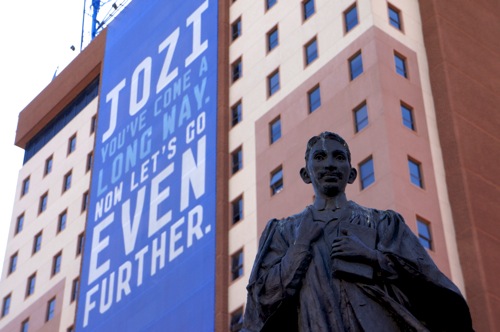

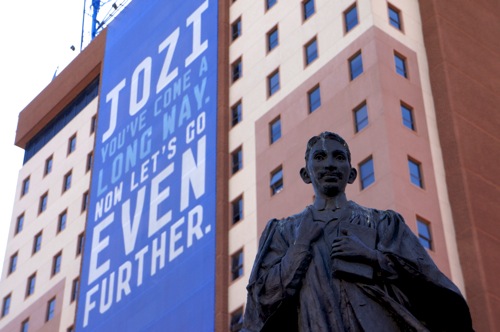

We have arrived in Gandhi Square, a large open space of bus ranks lined by lawyer's offices - the courts are nearby. Behind the bronze statue of the young Gandhi flutters a banner from the current council proclaiming:

'Jozi, you've come a long way. Now let's go even further.'

|

| Gandhi would approve |

Much of the regeneration of this historic square has come for the unlikely direction of a law firm (

Olitzki) that took over many buildings in 1989 and has been involved in preserving both Gandhi's- he practiced law here before going to India to overthrow the British colonialists - and Mandela's offices - who also practiced law here before his arrest and imprisonment.

|

| The regenerated Ernest Oppenheimer Park |

Our walk ends at the Reef hotel, with the funky and cool

Gold Reef Cafe on the ground floor. We take in one more sweeping view of the city, this time from an opposite vantage point of the earlier Randlords' view. Gerald takes us through the recent history of the city, explaining the seemingly sudden abandonment of the centre for the suburbs - and the new centre of Sandton. There was an element of self-destruction involved in the legal restrictions imposed by the Apartheid government to control the movements of the black majority. Laws to limit how many black workers an industrial businesses could employ if they had their factory in the city caused major problems. The number was six. With the introduction of the laws manufacturing businesses were forced to relocate. Large factories left the CBD, abandoning the southern area's industrial zone. Pass laws restricted blacks to homelands in rural areas, and only those that had a job were allowed into the city. Since the factories were forced to move out, there was no access to the city for black workers or shoppers.

|

| Chilling on the rooftops |

Then, in 1985, president Botha made a famously shocking speech called '

crossing the rubicon': in the face of international pressure instead of liberalising he clamped down on the anti-apartheid movement, made South Africa a military state, and declared a state of emergency. In expectation of the coming sanctions all international businesses left the city, leaving empty offices and ruined support businesses behind. At the same time the city workers left the northern city suburbs of Hillbrow and Yeoville, then bustling middle-class neighbourhoods, following the direction their workplaces had taken. Vast numbers of flats were unoccupied. Landlords keen to keep their income allowed flats to be occupied by poorer tenants, who turned to overcrowding to finance their new homes. The local municipality turned a blind eye because it disagreed with apartheid, allowing the deterioration of properties. In a few short years at the end of the 80s Jozi CBD turned from world metropolis into ravaged slum.

We leave Gerald's tour here to return to Braamfontein, exhausted and enlightened in equal parts by this half day wander through the city. He will take the rest of the group on south and then return to Braamfontein by bus. I am left with a head buzzing with all the new impressions. It seems that every time I brave the CBD I see a new and fascinating part of it. There is the student hipness of Braamfontein, the cultural hub of Newtown, the hip lifestyle centre of Maboneng, the unjustly neglected art gallery and Joubert park. Now I can add the intriguing shopping streets of Kerk and Eloff streets.

You can find more photos in my Flickrstream.

You can find an overview of Jozi walks here, my account of a guided walk in Melville here, a Yeoville walk here, an account of instawalking here and my story of photowalking here