I’m reading Ken Follett’s

Pillars of the Earth right now, which inspired me to learn more about cathedral building. As it turns out he wrote the book for the same reason. He grew up in a born-again Christian family and never entered a church in his childhood. When he visited Winchester cathedral for the first time, he became obsessed, turning into a cathedral nerd. The book is very descriptive on the process of building a church of that size in the 12th century, detailing not just the design and building process, but everything from funding to politics.

Armed with a book on

How to Read Buildings (subtitled “A crash course in architecture”), we braved the rain and high winds of yet another winter storm and drove the hour and a half to Winchester. We threaded our way between the South Downs on our left and the seaside resorts of the chalk coast on our right to Portsmouth, then turned inland to Winchester. Only last week we watched a BBC documentary on King Alfred, considered the first Anglo-Saxon king (whose bones were interred in the old minster which used to sit right next to where the new cathedral now rises), so the huge statue of him with sword raised in battle on a plinth at the entrance to the city didn’t come as a surprise. What was a surprise was the massive size of the cathedral.

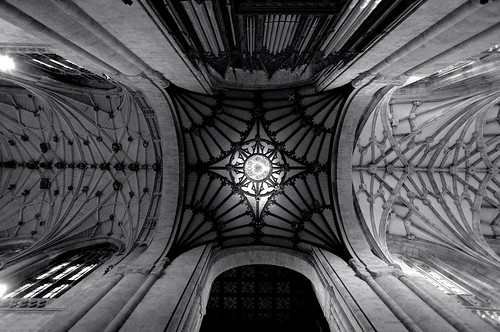

We ducked into the front door out of the driving rain, shivering with cold. I was regretting going out at all instead of sitting on the sofa with a cup of tea and my knitting. An afternoon spent in a cavernous and chilly cathedral seemed like bad judgement. But when I pushed back my rain hood and lifted my eyes, I forgot my damp jeans and freezing fingers. My grumpy thoughts were replaced by awe. I stood at one end of a ginormous, vaulted hall. Large grey brown flag stones spread under my feet, frequently interrupted by granite black grave markers. Over my head the span of gothic fan ceiling seemed as far away as heaven. At the far end of the space I could just make out an intricately carved wooden separator. Pillars marched away from my viewpoint on either side of the wide empty nave. In winter the cathedral is emptied of seating to present the church in the way it was intended to be seen: a vast, impressive display of celestial power manifested through the local bishop, a place to marvel at human achievement in the name of god. It brought tears to my eyes.

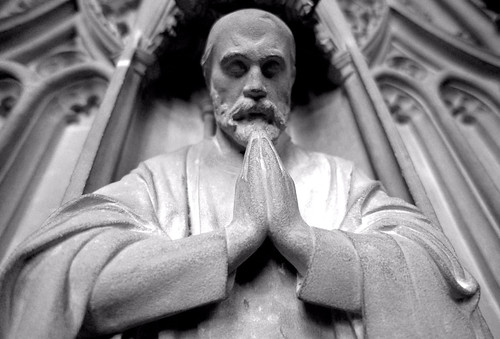

|

| Mini monks praying for their bishop |

Reading The Ken Follett book I have a fresh image of life in the 13th century. Winchester cathedral was built at just that time. I squinted, trying to imagine how the building work might have been achieved. The height of the barrel vault made it seem impossible to construct with just the use of wooden scaffolding. How would the masons been able to span the pillars lining the nave to construct the centring that holds up the stone arch as the mortar dries? How would they have lifted up the heavy carved keystones? How would they have calculated the depth of the foundations and weight of the buttresses to steady the aisle walls so the ceiling didn't collapse? Now that I know the primitive materials and tools they worked with it seems even more miraculous that these cathedrals were ever built.

At first we wandered along the aisles, reading the grave markers and memorial plates. While looking for Jane Austen, who was buried here in an early morning ceremony (church service was at 10, so the funeral had to be done by then), we discovered many fascinating people: the officer who drowned after his supply ship blew up and sank during one of the colonial wars of the 19th century; the wife of a dean who described her virtues at great length despite starting by saying: "words cannot describe her"; the smart and kind and ambitious women whose accomplishments can only be read between the lines of 'feminine character' and 'extraordinary mind'; the officer described as 'angler, thinker, soldier'.

|

| Jane Austen's memorial plaque |

We found Jane Austen's grave. The stone plate makes no mention of her profession. She was not well regarded as a writer when she died, two of her books being published posthumously. But there are two more memorials to her, witness to her rising population as the 19th century discovered her skills: a brass plaque paid for by her nephew, who wrote her biography and praised her writing, and a later stained glass window funded by public subscription. The window depicts oblique references to her, such as St. John and his gospel which starts with: "In the beginning was the word..."

|

| A screen of holy fruit: figs, grapes, pomegranate |

We found other treasures in our slow meander through the cathedral: the largest medieval tiled floor, faded patterns of terracotta and cream; a bishops grave, three gnome-sized monks sitting at his feet praying; another grave, this one a Vanitas, with a gruesome skeleton topping the coffin instead of an elaborately dressed clergyman; a Romanesque transept, so different in its squat style from the elegant gothic - an opportunity to crack open the architecture book and learn something about rib vaults and shouldered arches and moulded capitals.